As a teacher, my goal has always been for my students to learn successfully and with enjoyment. In my efforts to support them, I have:

- provided (and sometimes created) materials at their language and reading level.

- asked questions in language that they can understand and successfully answer.

- predicted their answers, planned how to address wrong answers and to improve the language of correct answers.

- given each student as much time as he or she needed to learn the language and information necessary to discuss the topic and demonstrate mastery of the objective.

All this effort, and somehow, I hadn’t included rigor. I learned about this education trend during my formal evaluation with my principal when she asserted that my lessons lacked rigor. She went on to give examples to support her statement, but I was trying to silence the panicked objections that exploded in my mind when I heard the word rigor.

Obviously, this principal was unfamiliar with the challenges of students with hearing loss. They need gentle, supportive instruction. They need structured, scaffolded learning. They need compassionate support. And rigor sounds so … hard and unforgiving.

Now I wonder when and how I developed this image of my students as so fragile. It turns out that they are not fragile at all. And rigor is exactly what my lessons needed.

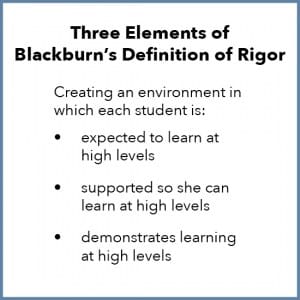

What is rigor? In her book, Rigor is NOT a Four-Letter Word,” Elizabeth Blackburn offers this definition:

Creating an environment in which each student is expected to learn at high levels, each student is supported so he or she can learn at high levels, and each student demonstrates learning at high levels.

How do you introduce rigor to a pampered class? First, introduce the Growth Mindset.

Before students are ready to take on rigorous lessons, they need to know that everyone faces challenges on the way to successes. They need to develop a trust for their teacher and their classmates. They need to understand that mistakes and failures will happen and are part of the learning process.

I used a familiar behavior management app, https://www.classdojo.com/. They created a series of animated videos that explain to students that learning requires effort, is difficult sometimes, but is very rewarding in the end. This is the Growth Mindset.

Then Embrace the Grapple

I began with math, abandoning the familiar Gradual Release model (“I do. We do. You do”) and challenged my students to enjoy a good “grapple.”

For me, the word grapple conjures images of alligator wrestling. It is better described by the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics as “productive struggle.”

I was told to give the students an unfamiliar problem that they don’t know how to solve. This sounded counter-intuitive, unfair and even a bit unethical. But I trusted my principal in the same way I ask my students to trust me.

So I explained that our principal wanted us to change the way we teach math. I told them it would be difficult at first, but that I was confident they would accept the challenge and do their best. And they did!

The basic structure of my math lessons now is “You do. We do. You do.”

- Students grapple (independently, in pairs or teams), trying to solve a new type of problem, then discuss their strategies.

- Teacher models problem solving, while thinking aloud. Students imitate teacher’s strategy and thinking aloud at each step in the problem.

- Students solve a similar problem, then discuss their strategies. Teacher addresses misconceptions and language.

- Students work independently to solve similar problems.

Here’s an example of one of our early grapples. To introduce multiplication, I gave students the following problem and told them grapple with it for 3 minutes.

Jose has 4 mangoes in each of his bags. There are 5 bags of mangoes. How many mangoes does Jose have?

I set a timer for 3 minutes, which was visible to the students. When the timer sounded, each student explained how he or she tried to solve the problem. The first student said, “I added 4 and 5, so there are 9 mangoes.” He couldn’t explain why he added. Another student said, “I subtracted because there are 5 bags but 4 mangoes are in the bags, so 1 mango is left.”

Benefits of The Grapple

#1 The teacher learns.

By letting the students struggle, I learn their strengths and weaknesses. They calculated correctly but didn’t read the problem carefully enough to understand it. I now require my students to draw a picture during their grapple time. Then they have to explain how the picture relates to text of the problem and to their calculation. They use sentence stems like those below to explain their thinking.

Sentence stems:

I drew (number) (objects) because the problem says ______________.

Then I _(added, subtracted, multiplied, divided)_because the problem says ________.

They still make mistakes, of course, and that’s when I learn even more about what support they need.

#2 The students learn.

This was the biggest takeaway for me. They learn so much from grappling!

They learn that everyone struggles because they are all being asked to solve a new kind of problem.

They come to see their own progress. I imagine this thought bubble over their heads: “On day one, I couldn’t solve this problem. But on day two, she gave me the same problem and I can solve it now! I can even solve other problems like it!” This visible growth makes the challenge worth the effort.

By grappling with challenging problems, my students have become more resilient. They now embrace challenges and even find them fun, because sometimes they do get it right the first time, and that feels really good!

Want to Read More?

More about rigor:

- What is academic rigor? “Rigor is pushing yourself beyond what is easy.” https://www.huffingtonpost.com/lori-ungemah/what-is-academic-rigor_b_1686412.html

- “… appropriately rigorous learning experiences motivate students to learn more … while also giving them a sense of personal accomplishment when they overcome a learning challenge—whereas lessons that are simply “hard” will more likely lead to disengagement, frustration, and discouragement.” https://www.edglossary.org/rigor/

More on the growth mindset :

- Decades of Scientific Research that Started a Growth Mindset Revolution https://www.mindsetworks.com/science/

- “Students who embrace growth mindsets—the belief that they can learn more or become smarter if they work hard and persevere—may learn more, learn it more quickly, and view challenges and failures as opportunities to improve their learning and skills.” https://www.edglossary.org/growth-mindset/

More about teaching math:

- Teaching Through Problem Solving

Julia West, MSSH, CED, received her Masters of Science in Speech and Hearing Sciences from Washington University. During her 22 years as a teacher at CID, she worked mostly with students in grades 2 through 5. Julia is currently a teacher of the deaf for grades 3 – 5 in a public school in Florida. She also writes the monthly Listening Strategies article for the Teacher Toolbox magazine at www.SuccessForKidsWithHearingLoss.com.